The Merger Verger just returned from M&A East, perhaps the preeminent middle market acquisition event of the year in this part of the world. M&A East is put on by the Philadelphia chapter of the Association for Corporate Growth and is very well done and very well attended.

While most of the attendees come for the rich networking opportunities, there are also work sessions and presentations … actual “content.” The Merger Verger attended one roundtable session dealing with the large role that the Buy-and-Build strategy and add-on deals are playing increasingly in the private equity world.

We noted a number of interesting or useful points:

We noted a number of interesting or useful points:

- The Buy-and-Build investment strategy has both the advantages and disadvantages of focus: wisdom, experience and increasing market power and multiple arbitrage on the upside; concentration and lack of diversity on the down side. Pick your poison.

- Market fragmentation can be an important attribute of a sector appropriate for Buy-and-Build but it requires some perspective and caution (read “better due diligence):

- Is fragmentation the result of incremental market development over time or some fundamental customer or sourcing requirement?

- A market that has long been fragmented may have an entrenched fragmented purchasing process on the customer side, making the synergy potential of national footprint harder or slower to realize.

- As fragmentation decreases through consolidation, multiples can skyrocket.

- Once the fragmentation has been wrung out, where will the next generation of growth come from?

- Some fragmented industries that were mentioned as undergoing PE consolidation: landscaping services, specialty physician practices, industrial crating.

- Add-on deals don’t have to smaller than the core operation although The Merger Verger notes that the integration can be more subtly complex with the egos of the newer larger company clashing with those of the smaller original company. We’re bigger and stronger than you. Yeah, but we were here first, doing fine on our own, thank you.

- When doing add-on deals, the question of branding looms large. It is highly possible that a small local brand carries more value in its market than a larger, more visible one. Landscaping services was an example of this.

- On the question of making acquisitions during economic downturns, most of the roundtable presenters felt that it was important to carry on. One presenter saw downturns as an opportunity to average down their purchase multiples.

- Conversely, both presenters and attendees noted that many middle market sellers don’t pay that much attention to multiples; they focus on price. (Multiples do not affect a seller’s retirement plans; raw dollars do.) In that context multiples can get ugly in a downturn.

- While the topic of integration was listed on the agenda, it got – as it often does – a short shrift. There is still this sense that getting through closing is the Win. It is not. The Verger repeats: you will have a vastly more predictable and successful outcome if you actively manage the “hows” of integrating your add-on deal:

- How are we going to realize the strategic intent behind this deal?

- How are we going to avoid the identified risks factors?

- How are we going to keep the best producers of the target company?

- Exactly how are we going to get our products selling through their channels?

- How are we going to make their square product design (or production or management or culture or sales) peg fit into our round hole?

- Seller-entrepreneurs like the Buy-and-Build strategy:

- They believe the buyer better understands “their baby”

- It’s easier to get buy-in on visions and plans and investment

- If the deal involves contingent payments, they have more faith in the the potential payoff

- “Buy-and-Build” just feels a lot more appealing than “Slash and Burn”

Buyers like the B+B strategy. Sellers like it too. It may not be for every PE firm but it’s here to stay.

“Bravo,” says The Merger Verger. And Bravo to M&A East.

to keep a target out of someone else’s hands, “man up” and walk away. The truth is that too many good deals go bad. A bad deal (meaning one based on a bad strategy)? That is one trophy you can enjoy watching The Other Guy win.

to keep a target out of someone else’s hands, “man up” and walk away. The truth is that too many good deals go bad. A bad deal (meaning one based on a bad strategy)? That is one trophy you can enjoy watching The Other Guy win.

It begins with understanding how you, the buyer, function and then asking the questions you need to know to understand how to make you and the seller function together. If you don’t have the time to develop the “how” questions or probe the answers or enact the solutions yourself, GET HELP. You will tilt the otherwise very long odds of acquisitions in your favor.

It begins with understanding how you, the buyer, function and then asking the questions you need to know to understand how to make you and the seller function together. If you don’t have the time to develop the “how” questions or probe the answers or enact the solutions yourself, GET HELP. You will tilt the otherwise very long odds of acquisitions in your favor.

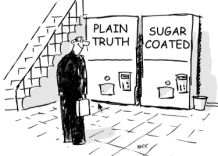

ersonal experience and he did NOT sugar coat it. If your target’s people are smart enough to do something that you want to have, then the chances are good that they’re also smart enough to see through sugar coating.

ersonal experience and he did NOT sugar coat it. If your target’s people are smart enough to do something that you want to have, then the chances are good that they’re also smart enough to see through sugar coating.

A thorough, effective integration process is an insurance policy … insurance against decades of past failures. That’s the problem: how do you measure the ROI on an insurance policy where the payoff is not measurable at the outset?

A thorough, effective integration process is an insurance policy … insurance against decades of past failures. That’s the problem: how do you measure the ROI on an insurance policy where the payoff is not measurable at the outset? talk itself is a highly important value driver. It’s anchored to four firm rules: no secrets, no surprises, no hype, no empty promises.

talk itself is a highly important value driver. It’s anchored to four firm rules: no secrets, no surprises, no hype, no empty promises.